Breaking down proteins: How starving cancer cells switch food sources

Cancer cells often grow in environments that are low in nutrients, and they cope with this by switching to using proteins as alternative “food”. Building on genetic screens, an international team of scientists could identify the protein LYSET as part of a pathway that allows cancer cells to make this switch. The findings are published in the journal Science.

Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins and key nutrients for cell growth and proliferation. Understanding how cells utilise amino acids is a central question in biology and especially important in cancer: tumours often have a limited blood supply, and to grow under such conditions, they can switch from taking up nutrients from the blood flow to breaking down proteins in their surroundings. However, the mechanisms that enable cancer cells to make this switch are not well-understood.

To study the molecular pathways that underly the switch, two groups of scientists with matching expertise teamed up: Wilhelm Palm of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg is a leading expert in cancer metabolism, Johannes Zuber at the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology (IMP) in Vienna brought in ample experience in functional cancer genetics. The scientists set up their study with tightly controlled nutrient conditions to mimic amino acid starvation as it occurs in many tumours. Then they used the “gene scissors” CRISPR-Cas9 to disrupt the expression of almost every gene in the genome, which allowed them to pin down several pathways involved in the nutrient source switch.

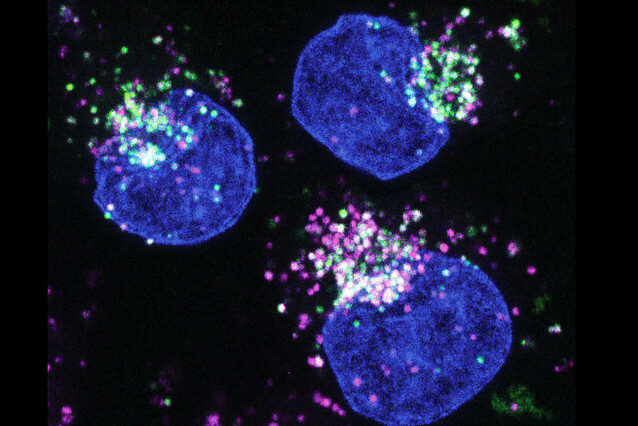

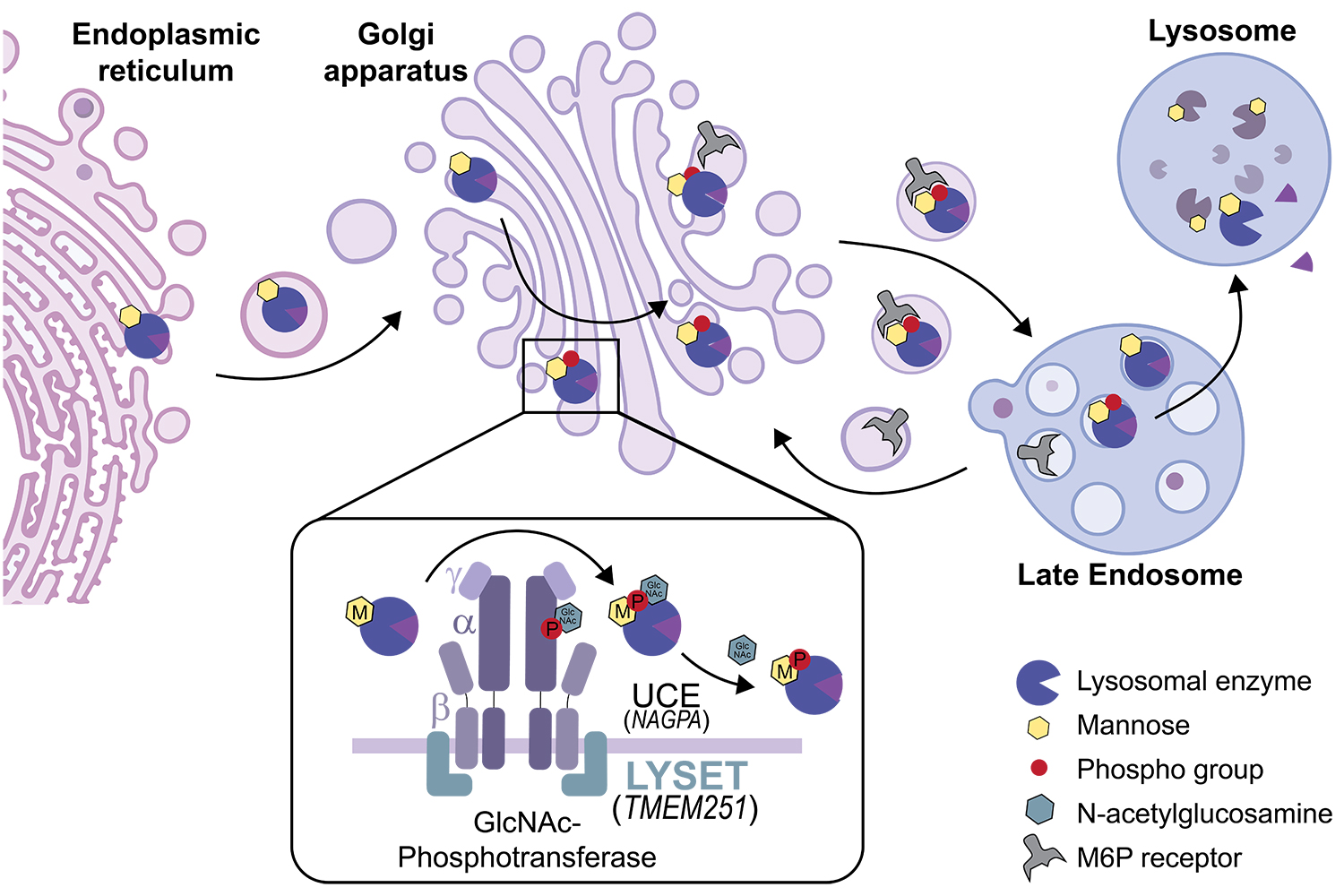

Among them, the scientists spotted an uncharacterised gene that was only required for cell survival when cancer cells were feeding on proteins. This gene, which the scientists re-named “LYSET” (Lysosomal Enzyme Trafficking Factor), turned out to be critical for the function of lysosomes, the regions in cells where proteins are digested. Further experiments into the functions of LYSET showed that it acts as a core component of the mannose-6-phosphate pathway, which is required for filling lysosomes with digestive enzymes (see figure 2 for details). In the absence of LYSET, cancer cells lack enzymes in their lysosomes and are no longer able digest proteins.

Then the scientists turned to mouse models to study the function of LYSET in real tumours. They found that the loss of LYSET strongly impaired tumour development in several types of cancer, while it was well-tolerated under normal nutrient conditions.

Wilhelm Palm, whose lab was among the first who described the ability of cancer cells to feed on extracellular proteins, says: “With LYSET, we have discovered a central component of a metabolic pathway that enables adaptations to different nutrients, a key ability of cancer cells to survive and grow in tumour environments that are low in nutrients.”

“This is what made the discovery so exciting,” says Johannes Zuber. “LYSET and the mannose-6-phosphate pathway turn out to be particularly important for cancer cells and could therefore be a molecular entry point for attacking a major metabolic bottleneck in cancer.”

Original Publication

Catarina Pechincha, Sven Groessl, Robert Kalis, Melanie de Almeida, Andrea Zanotti, Marten Wittmann, Martin Schneider, Rafael P. de Campos, Sarah Rieser, Marlene Brandstetter, Alexander Schleiffer, Karin Müller-Decker, Dominic Helm, Sabrina Jabs, David Haselbach, Marius K. Lemberg, Johannes Zuber, Wilhelm Palm:

“Lysosomal enzyme trafficking factor LYSET enables nutritional usage of extracellular proteins.” Science, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn5637

About DKFZ

The German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) with its more than 3,000 employees is the largest biomedical research institution in Germany. More than 1,300 scientists at the DKFZ investigate how cancer develops, identify cancer risk factors and search for new strategies to prevent people from developing cancer. They are developing new methods to diagnose tumours more precisely and treat cancer patients more successfully. The DKFZ's Cancer Information Service (KID) provides patients, interested citizens and experts with individual answers to all questions on cancer.

https://www.dkfz.de/en/

About the IMP

The Research Institute of Molecular Pathology (IMP) in Vienna is a basic life science research institute largely sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim. With over 200 scientists from 40 countries, the IMP is committed to scientific discovery of fundamental molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying complex biological phenomena. The IMP is part of the Vienna BioCenter, one of Europe’s most dynamic life science hubs with 2,650 people from over 80 countries in six research institutions, three universities, and 41 biotech companies.

www.imp.ac.at, www.viennabiocenter.org