A giant, snake-like enzyme seals the fate of unwanted proteins

A new study by scientists at the IMP reveals the structure of a massive, snake-like enzyme called HUWE1, and how it marks a multitude of undesirable proteins for degradation. Their findings, published in the journal Nature Chemical Biology, further our understanding of this enzyme and its therapeutic potential.

Of all molecules that float inside cells, proteins do most of the heavy lifting, yet they can be overzealous at times. To stay healthy, cells balance the amounts of functional proteins they contain with the help of a group of enzymes called ubiquitin ligases. These enzymes tag unwanted proteins with a label – the kind of label you stick on someone’s back as an April Fool’s prank that reads ‘hit me’. Other molecules in the cell recognise this label and destroy any protein wearing it.

In addition to their important role as quality control factors, ubiquitin ligases have recently emerged as a powerful medical tool: if scientists could reprogram them to tag a protein of interest – for example proteins associated with diseases – it could have tremendous therapeutic potential. To use these enzymes in such a way, it is crucial to understand the diverse mechanisms through which they operate and how they are safeguarded. One challenge lies in their enormous size, which makes it hard to visualise their structure and the way they choose their targets.

Some of these enzymes are very picky: they only tag a handful of specific proteins. Others, such as HUWE1, are generalists and have a wide range of targets - these are the most promising for medical applications, as they might be easier to repurpose.

Scientists in Tim Clausen’s lab at the IMP and in Dirk Kessler’s lab at Boehringer Ingelheim have investigated the structure of HUWE1, revealing its giant coiled shape and its unique modus operandi. Their findings are now published in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

An all-in-one enzyme

“HUWE1 is a large and flexible protein whose structure stands out among other known members of its family,” says Olga Petrova, contributor to the study and participant in the Boehringer Ingelheim postdoctoral programme. “It plays an important role in tagging proteins for degradation during cancer development, so visualising its structure with the latest technologies has opened up opportunities for potential drug design.”

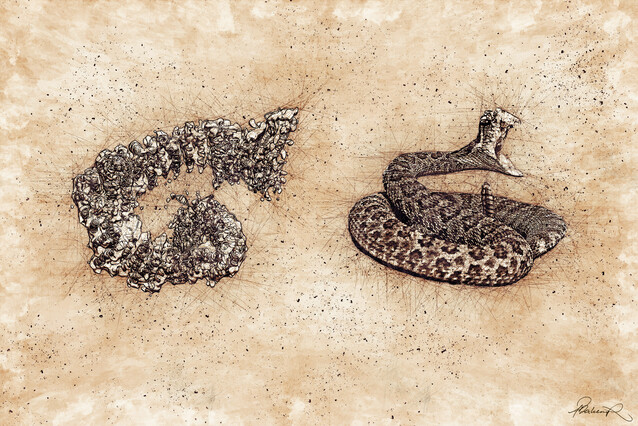

HUWE1 binds to its targets in unusual ways. While many ubiquitin ligases have few binding sites and use interchangeable ‘adaptors’ to attach to given proteins, HUWE1 carries a large array of binding sites at all times. These sites line a long, dynamic coil that gives the enzyme a serpentine look.

“A wide variety of proteins whose functions are unrelated fall prey to HUWE1,” says Daniel Grabarczyk, corresponding author and postdoc in the Clausen Lab at the IMP. “Unusually, HUWE1 may work both as a quality control for all superfluous proteins and as a selective labelling system for signalling proteins involved in cancer.”

Expanding a medical repertoire

“Ubiquitin ligases give their target proteins a ‘bite of death’, so to speak. Once proteins are labelled by HUWE1, they are rapidly eliminated from the cell,” explains Tim Clausen, senior scientist at the IMP. “If we can resolve the molecular details underlying target selectivity, we may be able to target a vast array of proteins that cause or result from disease.”

The scientists decided to study HUWE1 because it represents an ideal platform for potential drug design. It has a broad spectrum of targets and is present in all tissues and organs of the human body – in other words, malleable to medicine’s will.

The researchers’ next endeavours will be to develop small, synthetic molecules that act like sticky tape and ‘glue’ HUWE1 to proteins that need to be destroyed. HUWE1 and the targets would artificially interact, and the unwanted proteins would be forcibly tagged and eliminated from the cell.

Original publication

Further reading