IMP scientists solve first plant proteasome structure with supermarket spinach

What do you do when your preferred model organism lets you down? You innovate! Scientists at the IMP have solved the first cryo-Electron Microscopy structure of a plant proteasome using spinach from a local supermarket instead of cultured Arabidopsis – a yielding solution. The study, led by an undergraduate student, is now published in the journal Plant Communications.

Starting your own lab presents many challenges, the first one being to recruit students who are willing to join a brand-new team. When structural biologist David Haselbach founded his lab at the IMP in 2017, the first student to be by his side was Susanne Kandolf, a bachelor’s student from the University of Applied Sciences in Vienna.

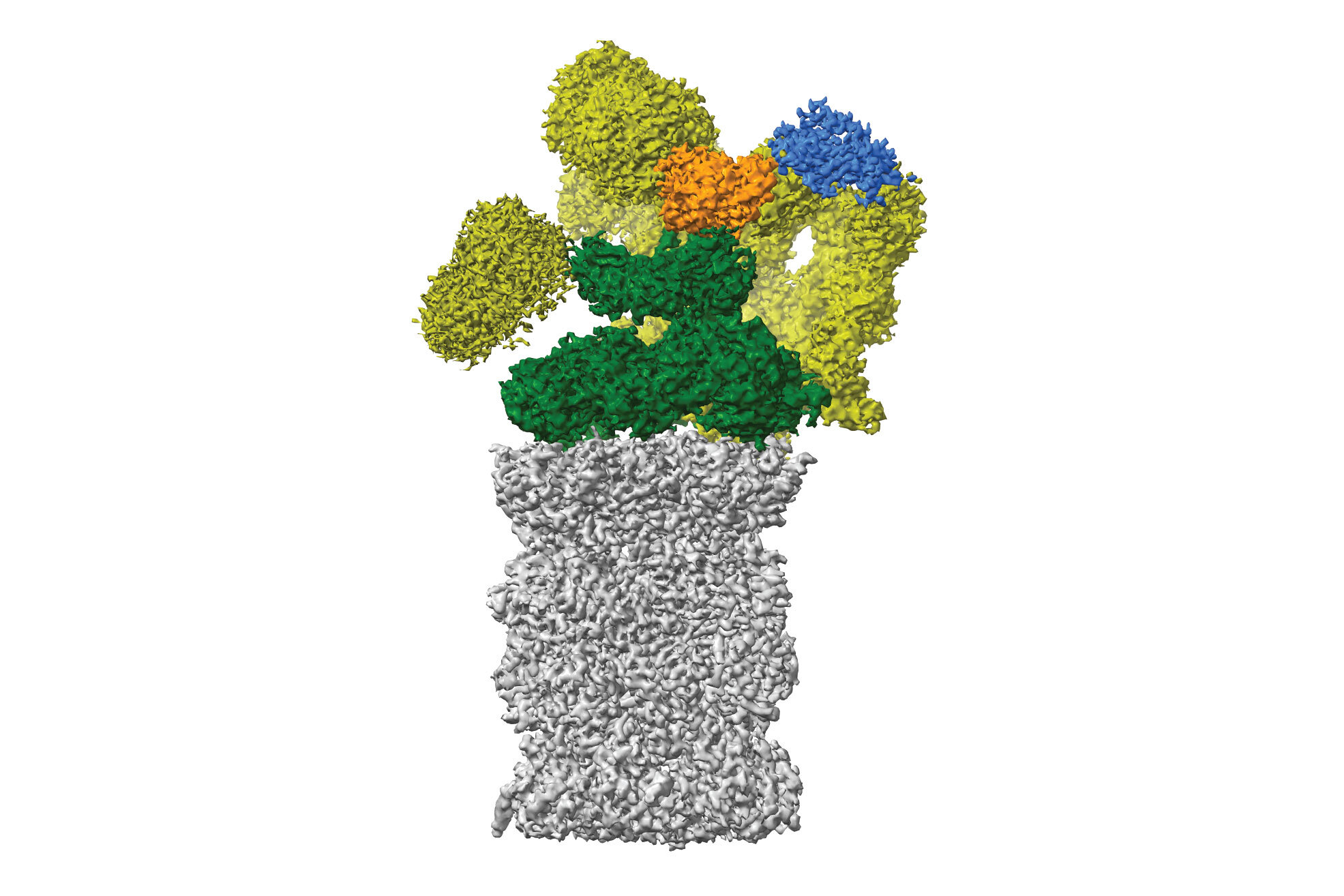

For her 12-week bachelor’s thesis, Susanne set out to solve the first structure of a plant proteasome. The proteasome is the recycling centre of the cell and dismantles unwanted proteins into small peptides to be reused later. While the Haselbach Lab has mainly focused on the mammalian proteasome, their side explorations of the plant kingdom have yielded new insights into proteasome biology, now published in the journal Plant Communications.

An unusual organism under the lens

For this project, the small team had planned to use a classic plant model called Arabidopsis, which biologists often use to investigate fundamental questions in plant physiology, development, and genetics. However, extracting enough proteasomes from tiny Arabidopsis plants proved cumbersome and expensive:

“We needed approximately one kilo of young leaves to get enough plant material, so it was clear that Arabidopsis from lab cultures wouldn’t do the trick,” explains first-author Susanne Kandolf. “We resorted to a most unusual plant – spinach – which turned out to be much easier and cheaper to collect.”

And so it began: Susanne headed to the nearest supermarket, where she bought out the stock of spinach, ground all the leaves, and started the extraction process. In the manner of Popeye the Sailor building instant strength after eating spinach, Susanne’s experiments gained momentum as soon as she switched model organisms.

“Within twelve weeks, Susanne managed to purify plant proteasomes from spinach and collected enough data with cryo-electron microscopy to infer the three-dimensional structure of this molecule,” says David Haselbach. “It goes to show that thinking outside the box is crucial to help a scientist out of a tricky situation.”

Characterising the first plant proteasome

The proteasome structure revealed in this study greatly resembles the proteasomes of mammals and yeasts, demonstrating that the basic architecture of the complex has not changed much in the course of evolution.

The few structural differences that the scientists observed, including a long ‘tail’ absent in mammals, have yet to reveal their functional secrets. The researchers also discovered a novel movement of the proteasome, which contracts and expands in the way of an accordion, possibly to help eject chopped-up peptides from the proteasome's insides. This study raises many functional questions – a project to be tackled by another student in the near future.

“My colleagues in the Haselbach Lab let me run the project from beginning to end, with a lot of support,” Susanne says. “Undergraduate students at other institutions rarely have such opportunities, so I am very grateful for this experience.”

Original publication

Susanne Kandolf, Irina Grishkovskaya, Katarina Belačić, Derek L. Bolhuis, Sascha Amann, Brent Foster, Richard Imre, Karl Mechtler, Alexander Schleiffer, Hemant Tagare, Ellen D. Zhong, Anton Meinhart, Nicholas G. Brown, David Haselbach. Cryo-EM structure of the plant 26S proteasome. Plant Communications (2022), doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2022.100310.

Further reading

Research in the lab of David Haselbach

IMP students characterise a sperm protein essential for zebrafish fertilisation