Stay positive – how the brain incites mice to react positively to both fear and reward

Neuroscientists used to think that positive and negative emotional states were processed in distinct areas of the brain. Mounting evidence from the past 15 years has challenged that view, showing that opposite signals and responses can be wired into the same anatomical structures. The lab of Wulf Haubensak at the IMP has investigated how fear and reward-seeking behaviours are encoded in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. They report in Frontiers in Neural Circuits that different circuitries process these emotional states, although they result in an overall positive response.

An animal’s brain receives a constant flow of information from the environment – should it be the smell of a delicious snack or the frightening sight of a predator. Responding to ambient stimuli with the appropriate behaviour is, in some cases, of absolute necessity for survival.

Scientists long thought that certain areas of the brain were dedicated to processing a specific positive or negative emotion. However, starting in the 2000s, accumulating evidence rendered this black-and-white view of neuroscience obsolete, leaving room for a more nuanced perspective. Some brain regions can process both positive and aversive stimuli: the amygdala, for instance, contributes to the processing of fear and reward, two opposite emotional states.

“We now have the tools to look at the way these responses are encoded at the cellular level,” explains Wulf Haubensak, group leader at the IMP. “Our main goal is to understand how neural circuits of opposite valence, positive and negative, are wired into the same anatomical structures.”

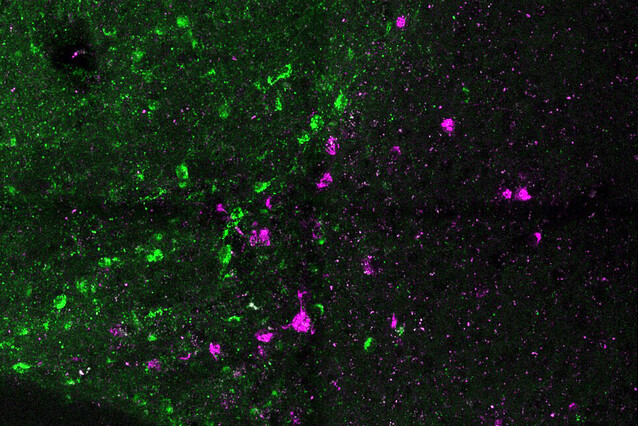

The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, or BNST, is a small neural processing hub located near the amygdala, at the centre of the brain. This structure has long been described as a key component of the fear processing machinery. In the past ten years, however, it has also emerged as a possible modulator for rewarding behaviours.

A team of scientists in the Haubensak Lab have researched how the BNST processes both fearful and rewarding signals, and how it relays these signals to other structures in the brain. They found that the BNST responds to both fearful and rewarding stimuli. However, its behavioural output to the rest of the brain has an overall positive bias towards suppressing fear and increasing reward behaviours, regardless of the valence of the input signal. Their findings are now reported in the journal Frontiers in Neural Circuits.

Positive and aversive stimuli tread different neural paths

The researchers used a classical conditioning method to study fear and reward-seeking behaviours. They trained mice to associate a specific sound to either a mild electric stimulus to their feet – an unpleasant surprise – or to a drop of sucrose – a beverage mice love. Once the mice’s brains had learned to associate a sound with a positive or aversive stimulus, the sound alone was enough to trigger the corresponding response.

Using this setup, the scientists were able to investigate the neural circuitry that processes and responds to these signals, teasing apart which groups of neurons are linked to fear, and which ones to reward.

“We found that specific neurons within the BNST process either fear or reward, but not both,” explains Nadia Kaouane, former postdoc in the Haubensak Lab and first author of the study. “Our results suggest that neurons that encode fear do not connect to the same brain region than those that encode reward states.”

Overall positive behaviours

Together, these BNST circuits sense both fearful and rewarding stimuli. Surprisingly, their outputs increase reward-seeking behaviours and reduce fear, thus transforming any input into a net positively biased output.

Why so much positivity? According to the authors, these circuit elements might help animals overcome fear and follow up on rewards, in the face of danger or stress.

“There is a fine balance between the fear and reward circuitries that modulates emotional reactions,” says Kaouane. “In humans, an abnormal neural activity in the BNST is linked to addiction and anxiety. It could be that these conditions stem from a disturbance in this fragile balance.”

Original publication

Further reading